Lingxi Kong (孔灵犀) is a fourth year student majoring in Greek and Latin at Columbia University. He met with the Dalai Lama on April 24, 2008, and wrote an essay recounting the meeting. The Chinese version has spread widely on the Internet, both inside and outside of China now. The following English text is also written by the author and is published by CDT with his permission:

After the turmoil in early March, China’s media heavily attacked the Dalai Lama as the sponsor of violence in Tibet, setting off a surge of nationalistic reactions among Chinese students and immigrants around the globe. Has the whole world been hoodwinked by the simple monk, or have we built up blind hatred based on distorted information? Either way, as a student supporting the Olympic Games and an individual who is determined to make contributions to the Harmonious Society, I do not wish to see Chinese and Tibetan people hating each other due to lack of necessary communication. With some questions and advice, I came to Colgate University and met with the Dalai Lama in a private house on April 24th, 2008.

In fact, after watching the turmoil in Lhasa on the Internet, some friends and I organized a panel discussion on Tibet in the International Affairs Building at Columbia University, where we included not only Tibetan speakers such as the Dalai Lama’s representative to the United States, the Director of Tibetan Youth Congress in US, but also scholars such as the Director of Modern Tibetan Studies at Columbia, as well as a political analyst representing the views of the Chinese government. It has been our firm belief that the best way to resolve bias and misunderstanding is through free exchange of ideas among people with different perspectives from all walks of life. The discussion lasted for three hours, with around one hundred and eighty attendees, including some of my friends and classmates, who, even at that time, had expressed their wish to hear the Dalai Lama’s positions towards the Olympic Games, Tibet’s future and the Youth Congress.

So on April 22nd, I zigzagged through the highway system without satellite signals, and managed to arrive at the very beautiful upstate institute, Colgate University, where His Holiness was giving a lecture on “happiness.” Five thousand eager faces crowded in the lecture hall where a fresh energy was surging through the air. Sitting in the ballroom between two large screens, he spoke slowly in a sincere manner. Despite making some occasional grammar mistakes, he was clearly a man of swift intelligence and great personal charisma. During the two-hour lecture, the main theme was always about compassion, pity, tolerance, understanding and forgiveness. After the event, when the audience was slowly dissolving into the beautiful campus with contented smiles, I saw twenty Chinese students waving national flags outside the lecture hall and shouting “We’re one family, don’t break it!” Due to a sore throat, I couldn’t engage in more communication with my fellow students, but I thought when seeing the Dalai Lama I would ask some serious questions that we all care about.

On the 24th, in Colgate Inn, a beautiful hotel with classic renaissance style decorations, after meeting several Buddhist students, the Dalai Lama was going to hold a news conference with Chinese media, including the Xinhua News Agency. He shook hands with each journalist as he walked into the small conference room, where some fifteen journalists representing ten media groups had set up their equipment behind the chairs. A female journalist not knowing the proper etiquette put a hada over his neck. Throughout the press conference, he explained his commitment to non-violence, his support to the ‘greater unity’ between Han Chinese and Tibetans, his promise of not-seeking-independence and his support for the Games, which he wishes to attend.

Finally at noon, we were led to the front yard of a two-floored house where a security check was operated in a friendly manner by some officers who, after asking where I am studying, were a little surprised by being boldly asked back where they are working. They were not those legendary CIA agents, but working for the State Department. At the door, the Dalai Lama and a Tibetan monk along with some staff from the delegation greeted us. Following Tibetan custom, I shook hands with His Holiness and offered him a hada which represents purity; he pronounced “huan ying (welcome)” in Chinese, inviting me to sit down on the sofa. I mentioned that the feverish emotions displayed by people discussing the Tibet issue are perhaps due to the limited information received and the lack of real heart-to-heart communication between Chinese and Tibetans, especially the younger generations. I was hoping to hear his opinions.

The Dalai Lama felt that this is a serious moment as both sides are too emotional, and explained the Tibetan sentiments from a historical perspective. Before Yuan Dynasty, Tibet remained relatively independent, not being part of any central administration. Even since Yuan Dynasty, from Tibetan point of view, the relationship between the emperors of China and Tibet is not like that between a subject and a ruler, but like the relationship between a priest and a patron. Tibet was an independent nation before the Liberation Army entered Tibet. Before 1949, taxes were not collected in Tibetan areas. Occasionally, some Chinese came like warlords and collected money, and created some trouble, burning down some monasteries, but the essential Tibetan life remained the same; there was no control or restrictions. After 1949, since the Liberation Army came representing the new government, of course very powerful and organized, Tibetan life in every field had some kind of interference or control. So in 1956, the reform started in the common area, which was good and necessary, but the manner of the reform, mainly class struggle, carrying the same manner as in the mainland, and was simply unfit for Tibet. Unlike that in mainland China, the relationship between landlord and peasants was generally like that between parents and children, with landlords often showing great compassion and care. During the reform, landlords were thrown into prisons, and in some cases serfs beat the landlords. In other cases serfs remained silent and kept crying. Then resentment came, and uprising started, from Tibet to Xikang in 1956 and 57, and then spread to the whole area in 1957 and 58. Numerous Tibetans were killed. A notebook that the Tibetans obtained from a Chinese military officer says that from March 1959 to September 1960, eighty-seven thousand Tibetans lost their lives in Lhasa. Several thousand Chinese soldiers were also killed. The whole event was “very very sad”.

In 1954 the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama both as representatives of the National People’s Congress went to Beijing and other cities from central Tibet. He displayed a moving voice when he remembered the scenes: “Chairman Mao was a great person, talking slowly with me, and very dignified, each word, occasionally some coughing, is really wonderful. I was so much impressed. During that period I also had opportunities to visit some heavy industries—since childhood, I had a keen interest in mechanical things, so I was interested in visiting big factories. At local places, party secretaries, vice secretaries, provincial governors and majors dined with us, drinking Maotai (the most famous Chinese liquor), though I couldn’t drink. I met all levels of officials and party members, many of which participated in the Long March. At that time, I was very interested in Marxism, so when I was in Beijing, I told communist party officials that I want to join the communist party. They told me to ‘wait a little bit’. In the summer of 1955, I left Beijing for Lhasa, and met Commander Zhang Guohua en route, a very nice person, Comrade Zhang Guohua, who was traveling from Lhasa to Beijing. I told him, ‘last year when I was traveling from Lhasa to Beijing, my heart was full of doubt and anxiety, but traveling on the same road back to Tibet now, I am full of confidence and hope.’

“At that time, not only I myself wanted to join the Communist Party, there were also several hundred Tibetans who already joined the Communist Party during the 30s and 40s. I knew a Tibetan Communist from my hometown, who had some injuries on the nose, who proudly stated to us that it was due to a Japanese bullet, because he participated in the Sino-Japanese war; he was a member of the Communist guerilla force. I was not a communist but almost like an alternate member. Now those Chinese, unlike previous Chinese, are revolutionary-minded, very caring about brotherhood, socialism and equality. The nationalists and the Manchurians always made differences between minorities. But these Tibetan communists really felt proud of being communists and part of People’s Republic of China. Chairman Mao made the Seventeen Points, in which one point mentioned Military and Political Committee. We were very afraid seeing the word ‘military’, but when we saw the frame of autonomy, everyone was very happy. Then in the year of 1956, Autonomic Region Preparation Committee was founded. Foreign Minister and Martial Chen Yi, who addressed up as a Martial in a big ceremony, actually, it was he who emphasized the importance of establishing a unified autonomous region. So what we refer to as “all Tibetan area”, which includes the whole Tibet, part of Sichuan,Qinghai, Gansu and Xikang, was first promised by Chen Yi.”

Telling from the Dalai Lama’s feelings and sentiments, he showed true sincerity in reminiscing about those veteran revolutionaries of the Communist Party, and cherished very much the relationship with the central government. I think without the Dalai Lama’s influence and advocacy for non-violence, it would not have been possible for people living in the area, where the Dalai Lama is being worshiped as the Living Buddha, to live without long-term, large-scale violence and bloodshed. On the other hand, if the Chinese government could heed the reasons and sentiments behind the long-standing resentment of the Tibetan people, so as to deal with Tibetan affairs with greater flexibility, then “Tibetan loyalty to Han Chinese will naturally come.”

While I was having a moment’s reflection, his staff reminded us that His Holiness had to go to the airport soon. So I hurried to proceed to the next part, which was the main purpose of my trip: seeking the creation of multiple communicative channels for exchange of views between Chinese and Tibetan people, which is of crucial importance for “minzu da tuanjie” (Great Unity of Ethnic Groups). I proposed to initiate an open-letter exchange between Chinese and Tibetan students, to be posted on a website with translations in both English and Chinese, so that both peoples (and the whole world) can explore each other’s feelings and sentiments. Television debate(s) may also be held between overseas Chinese and Tibetan students on an American television channel. He enthusiastically endorsed those proposals, adding that in times of crisis, instead of being antagonistic or hating each other, people may discuss and explore what is really happening. I also mentioned that a very good friend of mine, who is a computer scientist, volunteered to make documentary films on the life of Tibetan settlements in India. He was very happy to hear about it and asked his delegation to give full support. His Holiness also accepted the advice that whenever he visits a place abroad, he should meet local Chinese students and immigrants, promote the exchange of views and clear up misunderstandings, and accumulate grassroots support from Han Chinese.

Even in terms of the “Greater Tibetan Area”, he showed much room for further discussion. I advised him to return Tibet at any price, for the creation of two Dalai Lamas would not only bring too much controversy, but violence would also ensue, as his non-violence influence would fade and a Lamaist church outside Tibet would be accused of being out-of-touch. So a high degree of flexibility should be maintained, if not to abandon entirely the idea of “Greater Tibetan Area”. He responded that he welcomes any discussion regarding the issue, but the Tibetan people living in other areas have put all their hope, support and trust in him. Also in regard to language and culture, people living in Tibet and other areas are inseparable. What he hopes is that Tibetan people themselves make decisions on internal affairs, that the main posts in local Tibetan government should consist of Tibetans who know the language and culture, so positive outcomes may be ensured for protection of their religion, environment and the unique cultural identity. As for himself, he will not assume any position and will go into complete retirement, handing over all his authority to the local government after returning to Tibet. I think since the Chinese government successfully solved the Hong Kong and Macao issues with great political wisdom, ensuring their continued political stability and economic prosperity, would these also provide any experience or insights towards China’s Tibet policies? Under the Dalai Lama’s repeated promise of not seeking independence, the possibility of “Tibet governed by Tibetans” should enjoy plenty of room for consideration. Even if some details were disputed and hard to settle immediately, any constructive discussions and meaningful communications between China and His Holiness would be extremely worthwhile.

Due to time-constraints, I asked only five questions out of the nine ones that I prepared:

1. Do you seek independence? Why? He emphatically answered: “No! For our own interests. Economically, a strong China provides much benefit to six million Tibetans who may live much better and much happier joining China for another thousand years.”

2. Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Jiang Yu said at a press conference on April 8: “The Dalai Lama is the head representative of the serf system, which integrated religion with politics in old Tibet. The ‘middle way’ approach that the Dalai Lama is pursuing is aimed at restoring his own ‘paradise in the past’, which will throw millions of liberated serfs back into a dark cage.” So do you seek theocratic serfdom? He answered, smiling: “I think since many years, as everybody knows, that we never aim to restore the old system, and even the Dalai Lama institution, as early as 69, I made clear that this institution should continue or not is up to people.”

3. Chinese media portrays the Tibetan Youth Congress as a terrorist organization that supports violence, and also accuses Your Holiness and the Tibetan Youth Congress of operating on two sides together to split China. How would you explain this situation, and what’s your relationship with the Tibetan Youth Congress? “At the beginning, we thought the Youth Congress was very important, just like any youth organization in a community—youth is the basis of the future. But around 1974, we made up our mind that we will return to China, so independence is out of the question. Therefore, we must find a middle-way, not the present situation, nor independence or separation. But gradually, the Youth Congress becomes very critical towards our position of not seeking independence and separation. So right from the beginning (of course they are Tibetans and Buddhists who often come to see me), I made it clear that your stance is very different from ours. I also often criticize them because they’re not realistic.”

4. When you pass away and the new Dalai Lama is still young, based on what you know, who would most likely assume your position of advocating the ‘middle-way’ appeals? Also, do you think that Tibetan people will accept the China appointed Panchen Lama? “Hopefully, I think I may not be dealing with the question of my reincarnation. As for the two Panchen Lamas, I think the official one Tibetans generally are not very faithful to, so it’s for our mutual interest to avoid such controversies.”

5. China has made many investments in Tibet in the last fifty years. In your opinion, from now on, in Tibet, what are the most important things that China and international groups should devote their financial resources to? “The local people should get some benefit. That’s very important, and some portion must be shared for the constructions of the local condition: hospitals, schools and some economic projects. That’s I think really important.”

After the meeting, he sincerely stated while holding an Olympic T-shirt: “I feel very happy holding this, because right from the beginning I already support that the famous Olympic Games should take place in the ancient, most populated nation, that is the People’s Republic of China.”

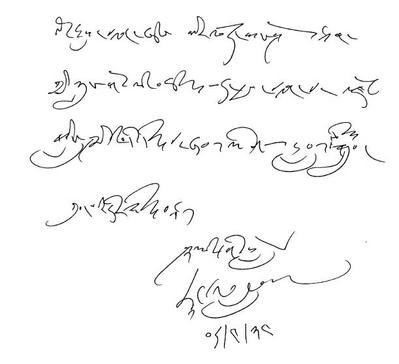

And wrote down the following message in Tibetan:

With an ancient civilization and the greatest population,

I pray that China achieves development and is able to provide

great contribution towards the welfare of the international community.

From the Shakya monk

the Dalai Lama

April 24th 2008

When I returned to school, my Tibetan professor told me that for “China” His Holiness uses the Chinese word “Zhong guo”, the People’s Republic of China, NOT the Tibetan word Gyanag, which means traditional China without Tibet.

The meeting lasted for roughly 75 minutes, and I was deeply impressed by his sincerity and hospitality. His advocacy for non-violence, support for the Games and promise of non-independence are all consistent with what he has said and done in the West. As an ordinary overseas Chinese student, I think not only the future of Tibet requires formal discussions between Chinese government and His Holiness, but to abandon hatred and to promote harmony between Chinese and Tibetans also require continuous dialogue and communication between the two peoples, and this is the main purpose of my trip.

Lingxi Kong

A fourth year student majoring in Greek and Latin at Columbia University

April 26th, 2008